Tyholland is the smallest parish in the diocese of Clogher. From the late sixteenth century, following the Reformation that occurred earlier in the century, Anglicanism began to establish itself in the diocese as the freeholders of the MacMahons, the main clan occupying this locality, were replaced by English servitors (men who served the king as government officials or soldiers). Miler Magrath was appointed as Anglican Bishop of Clogher in 1570 but only held the appointment for a year as he was translated to Cashel as Archbishop and no further appointment was made until the following century. Following the Plantation of Ulster in the early seventeenth century, Protestant numbers in the diocese grew and after the land settlements of the mid-seventeenth century much of the land in County Monaghan came into Protestant ownership with the establishment of large estates, such as those of the Coote, Anketell, Dawson and Richardson families.

Seventeenth century visitations of bishops of Clogher survive which record the poor physical state of churches in the diocese and that many church lands had fallen into lay hands. Some medieval churches were rebuilt for use by Protestant congregations and others were abandoned. An early reference from 1606 found the church at Tehallan in repair and in 1693 almost ninety years later it still appeared to be in some sort of repair. (Monaghan History and Society, ch. 15).

We know from a funeral entry of the Ulster King of Arms, quoted in Shirley’s History of the County of Monaghan, that in 1639 James de la Field of Derrynashalog, parish of Donagh, was buried ‘in the parish church of Tyalla’. He was the son of Robert de la Field of Knockboy, a townland in the parish to the south east of the church. In his will, dated 20 December 1638 and recited in a Chancery Inquisition, James de la Field besides stating that he wished to be buried in Tyholland, also desired that his executor build a chapel annex to the church 20×16 feet in which his body and that of his father and mother were to be reburied. Due to the disturbances associated with the Irish Rebellion of 1641 Shirley believed this annex was never built.

Jack Storey in his account of Tyholland Church Records, draws attention to the unrest in the Tyholland locality at the time of the 1641 Rebellion as told in the depositions of local Protestants which are now available on the Trinity College Dublin website. In his deposition, Hugh Culme, a gentleman who lived in the townland of Leitrim bordering the grounds of the church, recorded the atrocities perpetrated by the rebels who stole corn, animal stock and household goods from him. He stated that a priest Maccleary had declared that all the English in Monaghan should be hung. Richard Blaney, a local Justice of the Peace, was hung and the Rev George Cottingham, who was the Tyholland incumbent at the time, was imprisoned in very poor conditions.

Jack Storey also wrote of connections between the clergy of Tyholland and political events at the time of the late seventeenth century Williamite wars in Ireland. John Winder, who was rector of Tyholland for a very short period in the early 1690s, came to Ireland as a chaplain in the army of William III. He was also rector of Monaghan and a friend of Jonathan Swift’s.

A clearer picture of this ‘second church’ is revealed in the eighteenth century, as vestry minutes survive from as early as 1712. Eighteen century vestry minutes do not exist for many Church of Ireland parishes and for any historian researching this parish this volume of vestry minutes 1712-1828 is a significant resource. Of the sixteen parishes in County Monaghan which have lodged vestry minutes in the Representative Church Body Library for safe keeping, only three contain eighteen century minutes – Carrickmacross 1775-1989, Clones 1688-1974 and Ematris 1767-1984, so Clones is the only parish within this group with vestry minutes earlier than Tyholland.

This early volume of vestry minutes measures 26x20x3 cms but it is obvious that its contents have been rebound at some time in the past as text on the top and bottom of some pages is missing indicating that the pages were longer than the present binding. This is significant in one or two places where information has been lost or a signature is indecipherable as it has been cut off. A few pages have been bound out of sequence and there is a loose page containing details of two vestry meetings. Before the minutes begin there are two pages containing the name of each townland and its valuation. This valuation would assist the applotment or calculation of the payment of parish cess to be made by the inhabitants of a townland towards the running of the parish.

In most cases the vestry minutes were written up by the minister or rector at the time. This is evident when the hand writing is compared with that of his signature. On a few occasions the minutes are signed by a curate. The legibility of the minutes depends on the quality of the clergyman’s handwriting and the ink he used.

The incumbents (office holders) of this parish were both rectors and vicars of Tyholland as they held the cure or care of the parish, both spiritual and pastoral, as a prebendary. A prebend was a parish given to a canon or dignitary of a cathedral and the tithes of the parish formed part of his income. In the seventeenth century most of the incumbents of Tyholland, besides being canons of the cathedral, were also rectors of Monaghan. A rector received all the tithes of a parish while a vicar received only part of the tithes and was a deputy for the rector. Tithes were paid by the occupiers of agricultural holdings, both Catholic and Protestant. It was a tax of a percentage, usually a tenth part of their crops, labour and profits, used to support the Established Church.

The names of the vestrymen give some indication of the families living in the parish or at least worshipping at the church during the eighteenth century, for example Campbell, Eakin, Graham, Hannah, Hargrave, Johnston, Little, Speer, Stockdale, Williams and Young. Signatures of vestrymen contained in the minutes from 1712-1740s provide an interesting reflection on literacy among parishioners, for example in 1722 six out of the nine vestrymen signed the minutes of the Easter vestry with their own signature. Perhaps the fact that the parish had a school from the beginning of the eighteenth century influenced literacy among parishioners.

Easter or General vestries were generally held on the Monday or Tuesday after Easter Sunday. Their main function was to elect churchwardens for the next year. Churchwardens’ duties at this time were to keep order during services, to represent the parish legally and to keep the accounts. Sometimes the Easter vestry was adjourned for a short time, not later than Whitsunday, to give the churchwardens time to finalize their annual accounts. Churchwardens were paid a small fee, specified in later minutes for attending bishops’ visitations, and very rarely were appointed for a second term with the exception of Alexander Nixon Montgomery of Bessmount, who served as a churchwarden for almost twenty years in the early nineteenth century. High praise for one churchwarden was recorded on 17 Apr 1786, when the meeting resolved that the thanks of this vestry be given to Robert Wilson, the late churchwarden, for his proper conduct in his office & for making up the accounts to the satisfaction of the parish.

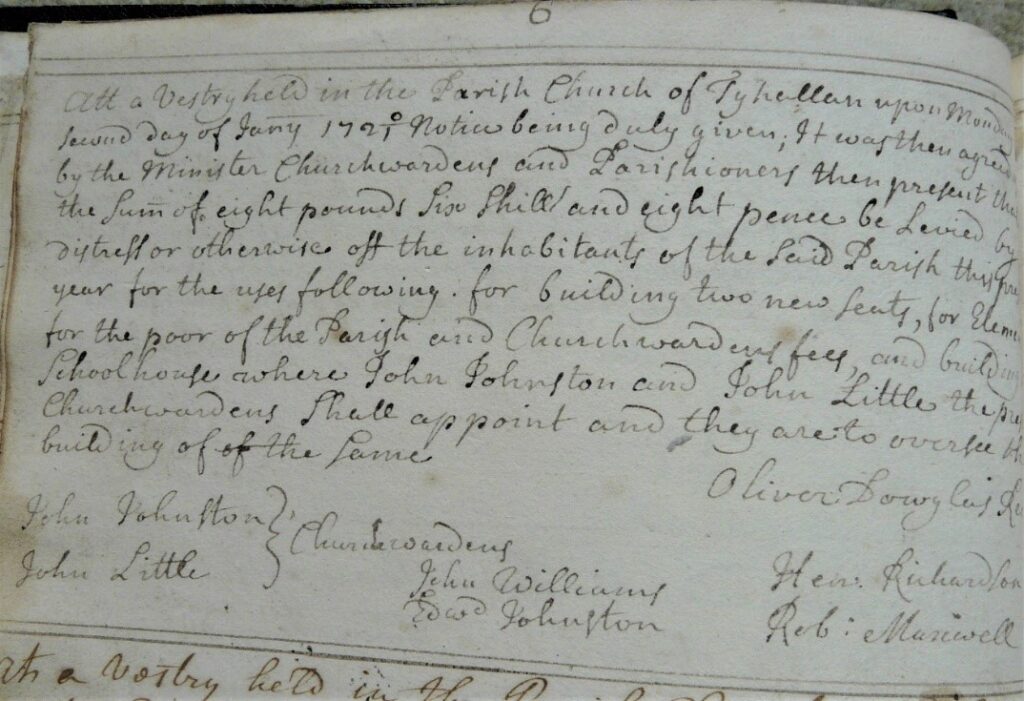

In the early years sidesmen or churchwardens’ assistants were appointed to help the churchwardens and applotters were given the task of collecting the parish cess. Parish cess amounted to between £2 and £10 in the early eighteenth century and by the 1780s was about £15. It was used to pay the expenses of the parish – the elements (bread and wine for communion); the salaries of the sexton and later the parish clerk and schoolmaster; payments to the churchwardens and applotters; repairs to the church and for the relief of the Poor and ‘other pious uses’ as recorded on one occasion. One other interesting thing to note on this image is the date of this vestry meeting held on the 2 January 1720/1. It draws attention to the use of the Julian calendar at this time. Under the Julian calendar the year started on Lady Day, 25 March, and ended on 24 March. In 1752, Ireland as part of Britain changed over to the Gregorian calendar which we use today.

Record of a vestry meeting held on 2 January 1720/1

One or two other vestry meetings were held most years, often to raise funds for a specific purpose. Under the ministry of the Rev James Hastings, which began in 1739, more detailed accounts were kept and so more evidence of parish spending is revealed.

The duties of the parish clerk at this time were to act as an assistant to the incumbent, to help at services and to lead the responses, while those of the sexton were to look after the parish buildings and perform minor duties such as ringing the bell and digging graves. Reference to the sexton’s fees are contained in the minutes almost from the start. By 1740, the sexton was being paid £1 annually and by the early 1780s this sum had risen to £2. In 1759, the sexton was named as George Boyd. There is no reference to the parish clerk being paid out of parish funds until the late 1740s but a parish clerk was certainly in situ as the clerk’s seat within the church is mentioned in 1718. The parish clerk was paid a salary of £5 from the early 1750s and is named for the first time in the minutes of 1758 as Edward Harton (28 March). A document in the Diocesan Registry records him as parish clerk and schoolmaster.

Sums were allocated every year for the use of the Poor and this included the support of orphans and foundlings. From the 1740s when the accounts become more detailed there are regular references to the maintenance of foundlings by the parish. Rewards were offered to any person ‘who will bring before any Justice of the Peace the reputed Father or Mother of a foundling’. (7 April 1740). The discovery of the parents would of course save the parish the cost of supporting the foundling. In 1742, the first mention of women is recorded when the clerk’s wife was remunerated for nursing a foundling and Isabella McKenna for finding the foundling’s parents. Cate McMahon was also caring for a foundling, as was Sarah McKenna for a male child found on the land of Knockboy in 1746. The following year £2 was paid to Mr Edmund Hill as an apprentice fee ‘with the late foundling Mary then 7 years old’. In 1749, a memorandum states that a female foundling ‘being 6 years of age is to be bound to Jo Cunning of Allkill until she is 21 years old’. So these apprenticeships were obviously used to save the parish the cost of looking after the foundlings. In the 1770s, a number of foundlings were sent to the Foundling Hospital in Dublin, not a pleasant place where four out of every five children admitted died. The maintenance of foundlings continued to be a parish expense into the early years of the nineteenth century.

As the Established Church in the eighteenth century, Church of Ireland parish vestries assisted in civil administration; besides caring for the Poor they were also responsible for the maintenance of local roads. The early vestry minutes of Tyholland frequently refer to overseers appointed for the repair of named roads in the parish. They were to be repaired by the inhabitants living in the adjacent townlands or tates ‘by the six day work’ or free labour, which is a reference to one of the terms of the Highways Act of 1614, whereby parishes were responsible for the repair of roads within their boundaries serving market towns, by the inhabitants giving six days of free labour annually. For example, at a vestry meeting held on 6 April 1724, the following highways ‘from Argenole Bridge to Kinard Bridge & from Killrif to Drumrutagh & from Tihallan Church to Ballyflossens Bridge’ were presented to be repaired by the local inhabitants ‘by the six days work’, Henry Richardson, Robert Maxwell and Edward Lucas to be the overseers. Once the Rev James Hastings began his ministry in 1739 road repairs are not referenced in the minutes. However, road repairs are mentioned once again in 1771 when a sum not exceeding £6.11.0. was to be levied on the parish inhabitants for the repair of the road leading to the church from the bridge of ‘Tihollan’.

From this volume of early vestry minutes we can learn something of the physical fabric of the parish church at this time. The minutes from 1716-1725 give the impression that the church was undergoing considerable renovations. The costs of flooring, a new pulpit, font and gate and the building of new seats and a porch are recorded, as are repairs to the roof, which was a regular parish expense. In 1732, John Akin of Tullynure, carpenter, was paid £3 for new ‘singles’, shingles for the church roof. Shingles were roofing slates or tiles, possibly in this context made of wood, as he was a carpenter, perhaps indicating that this church may have had a wooden roof. Items purchased included a vestry book and a register for marriages, christenings and burials.

In 1725, the new seats were allocated to various families from the neighbourhood and their location within the church is also given. Seats had previously been built for the minister and parish clerk in 1718 and 1719. In 1747, Richard Graham of Coolmain built a new seat in the church at his own expense and the family’s old one was allocated to Alexander Montgomery of Drumrutagh (Bessmount). In 1779, a seat was allocated to Mrs Elizabeth Johnston of Killyneill and her family. The first mention of the allocation of a seat to a woman.

In 1733, work began on the construction of a ditch to enclose the churchyard and glazing of the south window. Two copies of the Book of Common Prayer were also purchased. In 1750, a weather cock was bought for the churchyard gate and expenses included iron work on the east window done by Terence McKenna, the smith. Two years later shutters for the window were provided by Walter and Robert McBride. From the early 1770s, there are regular references to repairs to the church roof and also to the exterior of the church and east window. Some of these repairs were carried out by James Harlan. References to repairs to the church continue in the vestry minutes of the 1780s until the first mention of a fund for the building of a new church occurs in the Easter vestry minutes of 9 April 1787.

The other parish building, the schoolhouse, was also constantly in need of repair. It is obvious from the records in the Diocesan Registry that the parish had a school right from the beginning of the eighteenth century as a schoolmaster, Edward Johnston, was appointed in 1703. He was also the parish clerk. The schoolmaster had to be licensed by the bishop of the diocese so there are references to the appointment of Johnston’s successors John Little, William Clinton and Joseph McQuilkan in the following years. Perhaps the parish did not initially have a school building as in 1717, it incurred a cost of £2.13.6. for the building and repairing of the schoolhouse and in 1734 John Akin, the carpenter of Tullynure already mentioned, was paid the balance of £7 for building the schoolhouse. This building was thatched and in 1744 twenty two stooks of straw were brought to the schoolhouse to thatch the roof. There are further regular references to repairs to the schoolhouse in the eighteenth century vestry minutes but a schoolmaster is not mentioned until the early years of the nineteenth century.